Facebook Case Study 🌏🔬: Using AI to Regulate the Digital Ecosystem

The modern digital giants have data on scales unfathomable to the outside, so trying to understand how they manage deleterious information is an uphill battle.

This became an off-topic post, given the anti-trust suit, but alas we will have year(s) to talk about that, and I am not going to talk about that in detail here.

I came across these two blog posts from Facebook AI a couple of weeks ago (1, 2) and I knew it would make for a worthwhile post. The goal of this post is to make more precise any claims we have about Facebook’s technological platform in terms of hate speech, misinformation, and the technology used to mitigate them. This is intentionally a-political and a-emotional, and I encourage people to search for facts like these before fully believing any media narrative (all sides of the aisle).

Facebook’s traffic is immense. Billions of users (and more bots trying to gain access as a user) create more content than humans alone can monitor. This is simply a prerequisite to the conversation below and will be a fundamental truth of the internet — humans cannot look at all the content (and even if they can, it may not be ethical). This means, controlling content will fall heavily on automatic systems. There, computers make the first decision and users report other content (with a few other mechanisms for monitoring content in between).

As a brief aside, a big goal of “fair machine learning systems” is an idea of contestability, where a user with flagged content or actions can counteract the ruling of a system. Facebook is going in that direction, but I raise some questions in what they are currently deploying. I bring this up not to say hate speech should be contestable, but that internet companies regulating the open forum should have tools users can use to stand up for themselves.

For reference, Facebook has been using something called DynaBench (found via Twitter) to run a lot of its production test. Details of the system show that contestability may be possible, but is not in the fore of this product — it’s hinted at with vague words about including humans-in-the-loop of decisions.

With Dynabench, we can collect human-in-the-loop data dynamically, against the current state-of-the-art, in a way that more accurately measures progress, that cannot saturate and that can automatically fix annotation artifacts and other biases over time.

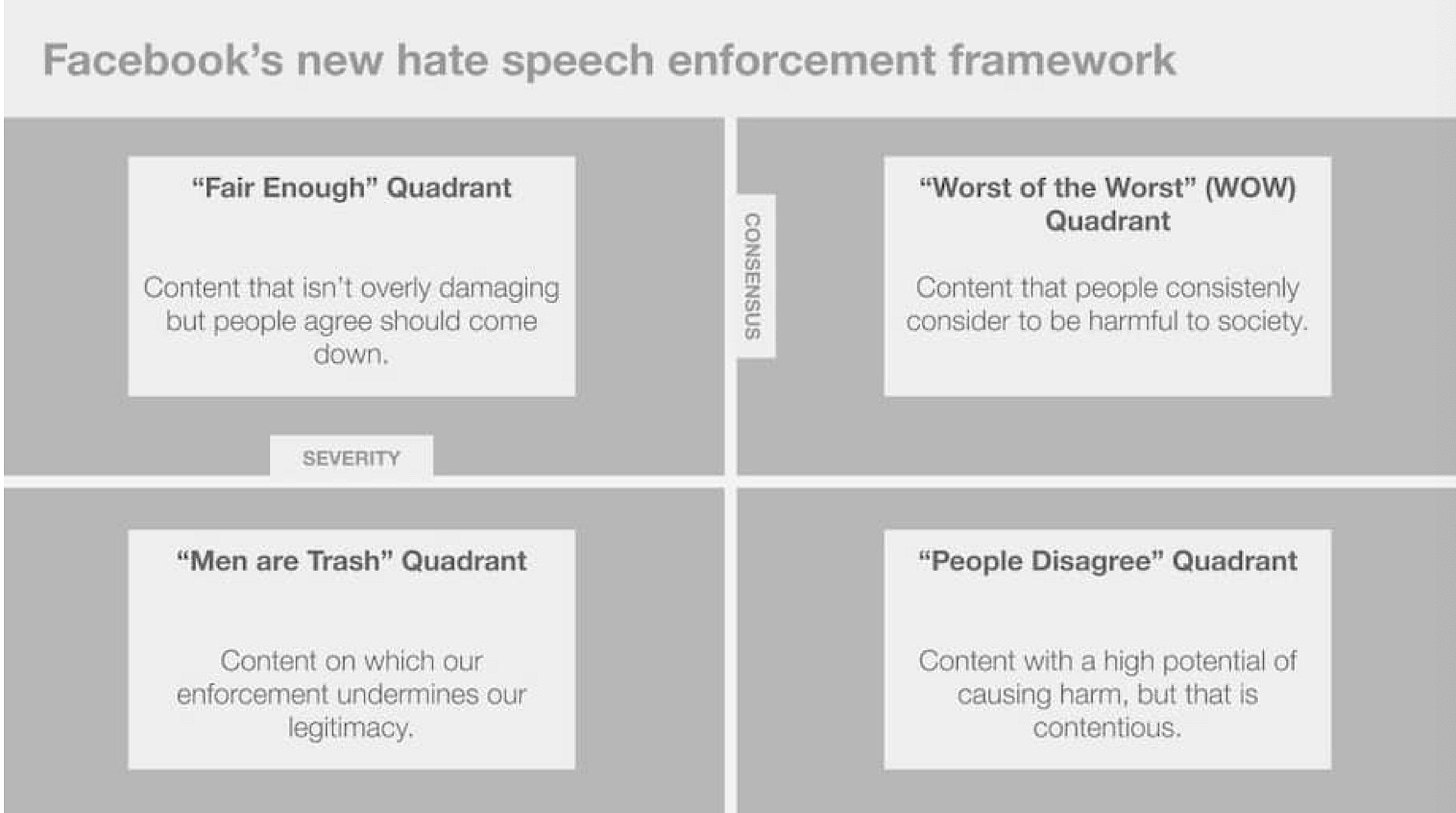

Okay, let’s dive into the policing of misinformation and hate-speech on the platform. As you can see below, the definitions are, interesting.

Facebook on hate speech

Facebook reports proactive detection of hate speech of 94.7% in Q3 2020 up from 80.5% in Q3 2019 (I would love to see earlier numbers if anyone knows where to find them). This is actually a substantial jump, given the scope of the problem described by Facebook below:

Detecting some hate speech is straightforward for both AI and humans. Slurs and hateful symbols represent obvious attacks on a person’s race or religion. But many instances of hate speech are more complex. Combining text and images makes it harder for AI to grasp whether the intended meaning is offensive even when a human might find it obvious. Hate speech can also be disguised with sarcasm or slang, or with seemingly innocuous images that are perceived differently in different cultures, regions, and languages.

A jump from 80.5% to 94.7% is covering 72% of the gap, where it is conceptually impossible to get to 100% (infinite possible ways to arrange speech, images, and videos). This was promising to me at first, but I am somewhat skeptical of their proposed approach — reinforcement learning.

Facebook’s new Reinforced Integrity Optimizer (RIO, actually RL :nervousface:) combines offline optimization with online experimentation to constantly validate the two.

Offline optimization is data cleaning, network structure, and parameter tuning (also called AutoML).

Online experimentation is enforcing decisions and seeing how users react to content.

The method passes gradients through these two systems to make an end-to-end approach. The problem is the article does not do a complete enough job describing what A/B testing is in the context of hate speech. The diagram in the blog post references metrics like advertisement clicks and user responses, which seems bizarre.

In the end, I worry that using RL here may just change the definition of hate speech. They do say that some hate speech is easy to detect, and they block certain words and phrases, but the intangibles are going to be difficult to monitor.

RIO uses a new large-language model technology called Linformer to use less compute (complexity of computation and memory used in Transformers to linear time). See the paper on Attention for more on how transformers et. al work. The idea is that the models learn which data-points to make connections to from a large potential set of connections (very data hungry, according to experts.). With multi-modal and self-supervised learning, Facebook is combining this technology to detect things like memes as well (see below a Facebook generated fake-meme).

Washington Post had a similar summary to this, which gave us the awesome image above ("Men are Trash" Quadrant). The metrics are better for Facebook, but I think this is mostly them closing the gap from no efffort to something and realizing a lot of hate speech is easy to detect.

The open question for me is: how does the difficulty of detecting hate speech correlate with the harm of said speech. We are in a relatively better place if the most harmful speech is the easiest to block, but I see no guarantees of that. I know the asymptote for harm doesn’t approach zero, and the difficulty to detect it can be very high. Leave a comment if you have any ideas.

Facebook on misinformation

Given the brutal election cycle, the pandemic, and the year 2020, there has definitely been more questionable information on the internet. Facebook does acknowledge this problem, but also openly does not want to be an artbitrar of the truth. I do see the political economy of large digital companies clashing with the largely liberal technology workforce in coming years if Congress does not pass meaningful legislation, but that is for another article. Here is how Facebook describes misinformation.

Facebook has implemented a range of policies and products to deal with misinformation on our platform. These include adding warnings and more context to content rated by third-party fact-checkers, reducing their distribution, and removing misinformation that may contribute to imminent harm. But to scale these efforts, we need to quickly spot new posts that may contain false claims and send them to independent fact-checkers — and then work to automatically catch new iterations, so fact-checkers can focus their time and expertise fact-checking new content.

Facebook’s blog post outlines a method of reducing misinformation that starts grand in scope, but narrows itself down to reducing repeated and similar content (and some stuff on generative models). This co-aligns with Facebook’s moot public facade on these issues — they want regulatory bodies to do this for them, but given the current political climate is unlikely. If misinformation is dangerous in the viral form, removing lookalikes will not prevent the viral harm to individuals and institutions (though, they have added restrictions to individual links too, which didn’t go well).

So, how do they do this? This paper on object embeddings in images is what the post points to (the most recent research is not public yet). This work and the blog are focused on matching near-duplicates and continual variation (lifelong variation of misinformation) with viral information — think if I screenshot an image and re-post it, it can detect it. This is done with technology (called SimSearchNet++ ) focusing on key objects in the content (memes often have varying backgrounds and common characters).

Facebook also spends time discussing their Deepfake Detection Challenge, but doesn’t do much in saying the scope of the problem on their platform. All in all, I consider the blog posts on misinformation to be much more lacking than hate speech. A better use of your time here may be scrolling through NY Times on Deepfakes, where they show how generated images can have unphysical objects like glasses with non-matched frames or differing earrings.

Philosophically, is hate speech a bigger problem than misinformation? I think misinformation definitely is lower on immediate harm, but long-term I think misinformation will be a harder problem to solve (optimistic we somehow clamp down almost all hate speech).

In conclusion

It’s good to see something from Facebook on this. When you read the articles it doesn’t sound like enough (and I openly acknowledge the problem is hard to parametrize). It would be good to see more clarity on why the problem is so hard and who is most at risk of Facebook’s approach rather than positive PR trying to say they are doing a good job.

It is also worth pointing out a counter narrative datapoint on Facebook's implementation of misinformation in Myanmar. In short, Facebook implemented new policies there and it received positive feedback. Shocker, it involved Facebook hiring employees to go to Myanmar for an election and help understand and mitigate risks. It’s encouraging seeing humans in the loop there, and success.

NeurIPS 2020 is this week, and if you don't care this is the one talk you should watch — effectively a movie on the potential effects of NLP, CV, and all ML. Hopefully, you find some of this interesting and fun. You can find more about the author here. Tweet at me @natolambert, reply here. I write to learn and converse. Forwarded this? Subscribe here.