Open models in perpetual catch-up

The open-closed gap, distillation, innovation timescales, how open models win, specialized models, what’s missing, etc.

Every 4-6 months a new open-weights model comes out that causes a clamor of discussion on how open models are closer than they ever have been to the best closed, frontier models. The most recent is Z.ai’s GLM 5 model, which is the latest, leading open weights model from a Chinese company. In the last 12 months the new part of this story is that all of the open models of discussion are coming from China, where previously they were almost always Meta’s Llamas. These moments of discussion are always reflective for me — for, despite being one of open models’ biggest advocates, I always find the narrative to be overblown — open models are not meaningfully accelerating towards matching the best closed models in absolute performance. The ~6month gap is holding steady.

At the same time, it’s worth discussing what happens as open models keep getting way better. Open models are staying far closer on the heels of the best closed models than I, and many other experts following the ecosystem, would expect. On paper the top three American labs — in Anthropic, OpenAI, and Google — have vastly more resources at play for training in research. In this world, many would have expected a more obviously growing margin between the best open and closed models. Raw research compute, data purchases, user data, etc. all are providing relatively fine margins. Maybe it’s the scaling laws log-linear relationship from compute to performance coming into play?

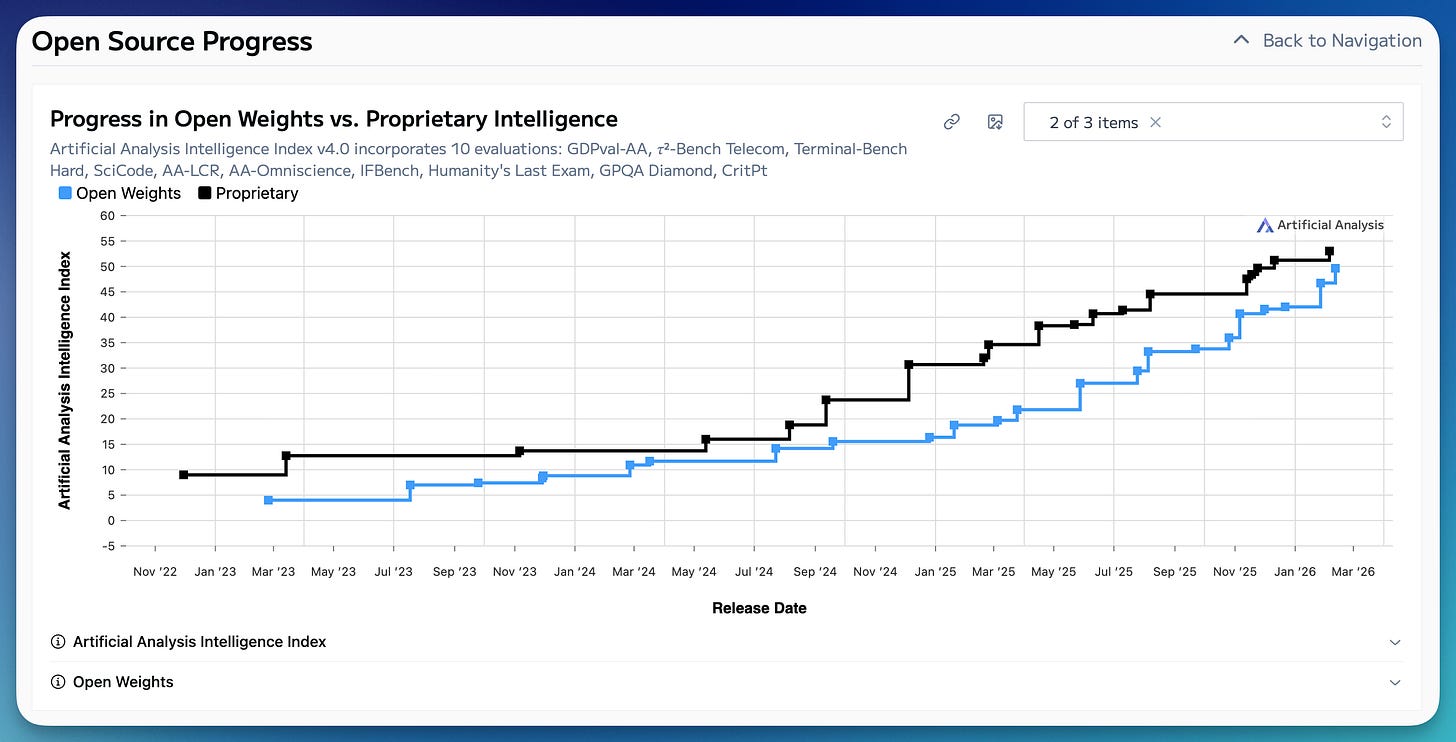

The plot of the day is ArtificialAnalysis Intelligence Index for open vs. closed models over time. The point of this post isn’t to nitpick this index’s many limitations, or any other, but to reflect on what this chart doesn’t represent and what it means for the AI world for open weights to keep pace year in and year out.

The benchmark mixes a ton of factors into 1 score that judges model “quality.” This compresses far too many error bars, stories, and weaknesses into one metric. These metrics will always be used to inform policy and help more people understand the high-level trends of AI, but they do a poor job of capturing the frontier of AI progress.

The frontier of AI has never been harder to capture in public benchmarks. Building benchmarks is now super expensive and requires extreme knowledge regarding the latest models and what they do and do not excel at. Well known issues like SWE-Bench being almost 3/4 Django or Terminal Bench 2 being crowdsourced and a bit noisy will never be captured here.

Time and time again it has been shown that the leading frontier labs in the U.S. have a better read on the capabilities that actually matter, and the public benchmarks tend to be a bit easier to overfit to. Qwen’s recent flagship v3.5 model has been plagued again with numerous complaints of benchmaxing (while some out-of-distribution weirdness is debatably implementation errors, on Alibaba’s own API).

The combination of all these factors has pushed me to advocate for “no averaging across our evaluation suite” when communicating the value of our latest Olmo models at Ai2 (see my recent talk on evals). The best models are indeed very close together, but averages can totally hide a single eval being dramatically different from an unscrupulous reader.

All together, I’d bet that the current Artificial Analysis Intelligence Index is a bit unrepresentative of the true frontier, rather than open models being closer to the closed models than ever before (yes, I know, it’s not like I am offering any obvious ways to improve it). The one domain where I foresee open models staying close behind is coding, where public GitHub data and clever verifiable rewards present a ton of potential performance gains.

The overall balance in the ecosystem is in between the value of the most intelligent model — which many people like myself still pay for despite open models’ improvements — and the incredible cost-reductions that come once a given task is achievable by a permissively licensed open model. The best closed models keep unlocking even more valuable tasks, keeping open models in a state of perpetual catch-up. The industry continues to reinvent itself at a blistering pace.

Onto the 7 biggest other trends in open models.

1. The open model frontier is brutally competitive

2025 witnessed a sort of “Cambrian Explosion” of open weight models with very impressive benchmark scores. This market is far more populated than closed, API based models (where there are 4 substantive providers), so open model adoption is brutally concentrated. Only the most-successful models ever get any adoption. This is going to push many small and mid-sized model builders across the ecosystem to shift to a specific niche or a different business plan over the coming months or years.

As a model builder, I feel this super close to home. Even though models are fairly sticky (at least more sticky than the general coverage would indicate) — many open models are set up once if performance is good enough, and never replaced – the likelihood for most models to even get tried once goes down month over month with the ecosystem getting more competitive.

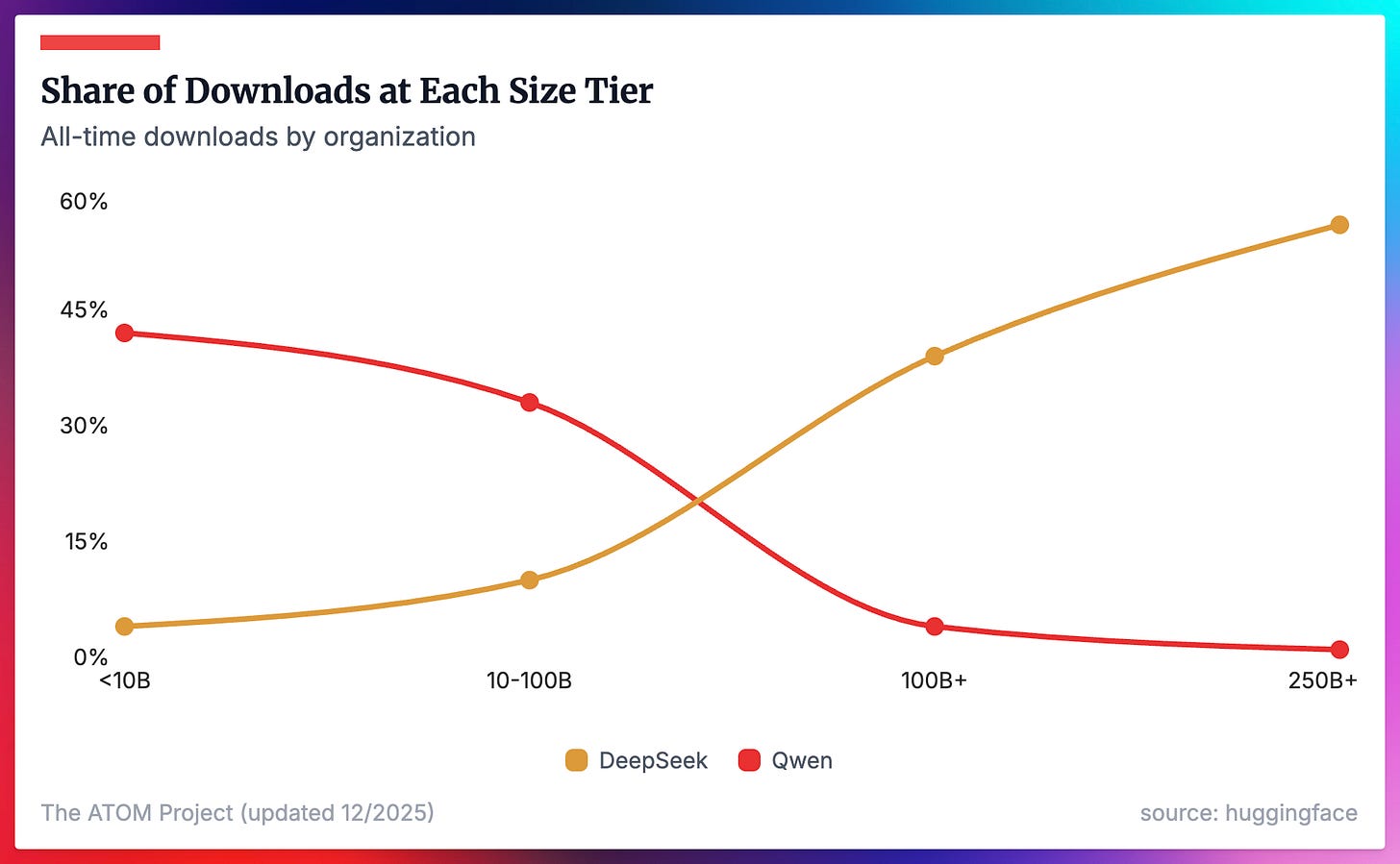

In my post on the state of open models earlier this year, I even learned that Qwen gets dominated on adoption metrics at the biggest scale of models. This continues to surprise me!

The upshot is that competition at the frontier of performance for models is most concentrated in the popular benchmarks of the day, especially with large MoE models — this will drive exploration and innovation towards other cases where open models can actually win on overall business value.

2. Specialized, small, fast, and cheap open models are missing

There’s a large underserved market in specialized models for the enterprise, particularly with tools (maybe GPT OSS’s success is somewhat related to this). Generally, the idea would be to either release the weights, or the method for creating them, that are excellent in valuable, repetitive tasks. With agents becoming more prominent, these models should be able to perform repetitive, agent sub-tasks at small percentages of the cost of large frontier models, while being faster, private, and directly owned. For example, what if one open weight model is deployed with multiple PEFT-adapters per skill, allowing high-utilization and extensibility.

I’ve specifically heard this request from multiple enterprises building agents. While the Qwen models are fantastic at small sizes, open models tend to be very jagged in performance, so multiple options would likely be needed to get this off the ground. It’s also limited by a general lack of frontier-quality, post-training recipes, especially when it comes to adapting a model to specific domain or set of tasks not covered in academic benchmarks. In this view, most of the domain-specific models of today, like math or biology models, are actually not specialized enough.

This is one of many issues that I see repeatedly in how the open model ecosystem has major blind spots. The biggest reason that the open model ecosystem seems a bit misunderstood externally, or confused in itself, is that open models take a long time to figure out and get into the world.

3. Understanding open models is massively under-indexed on

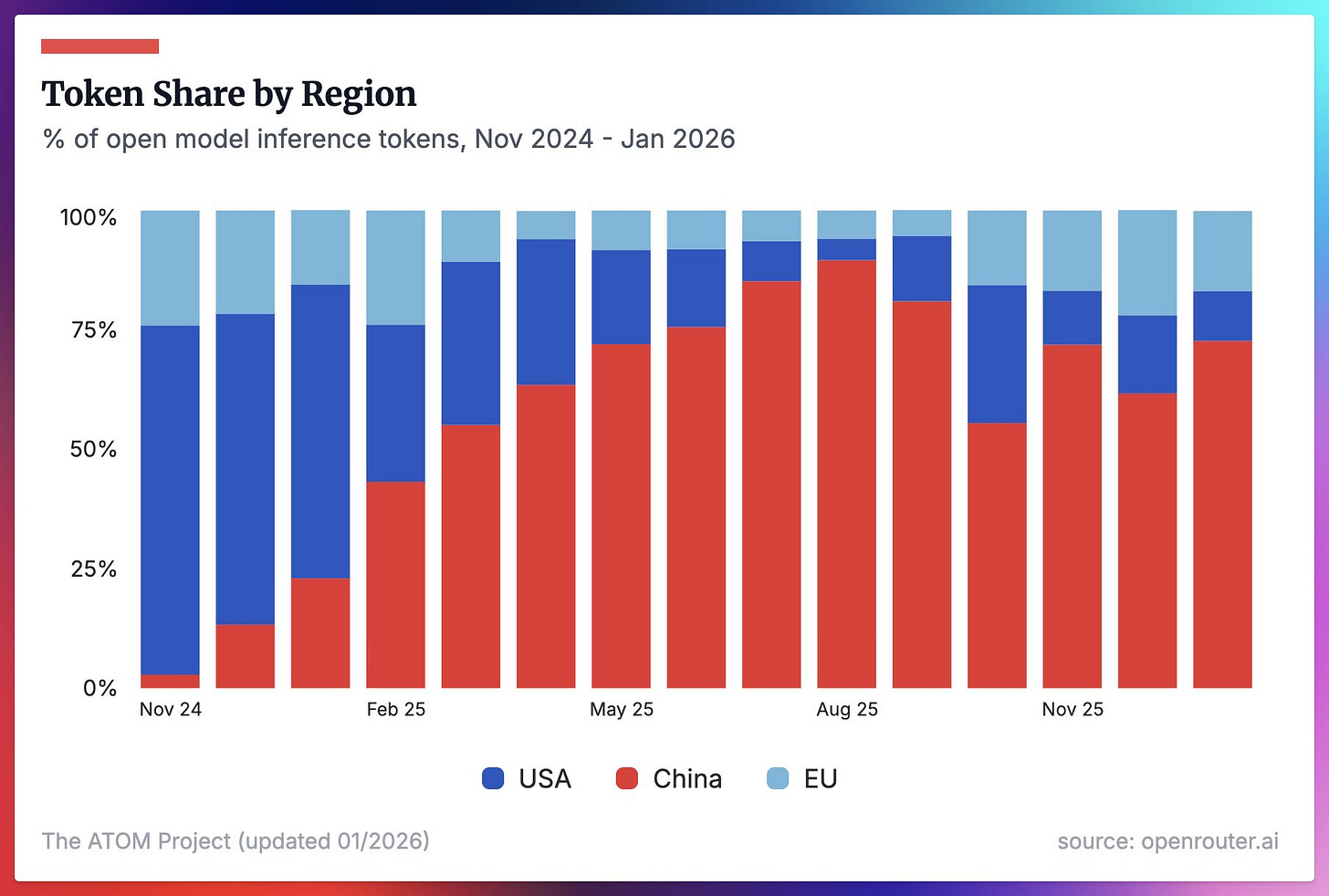

There should be more research organizations fully dedicated to understanding how open models work technically and geopolitically. There could be entire think-tanks in DC informing the public on what is happening, and uncovering information buried in hackathons and new research labs in San Francisco. For Interconnects and The ATOM Project I’m at the frontier of this work, which often entails uncovering new raw data on how open models are used. This data is always messy and imperfect, and often flat out confusing. Understanding open models is how we keep track of the direction of global diffusion for the most important technology in decades, and it feels like there is almost no public work doing so.

Here’s some new data on open model usage courtesy of OpenRouter, which largely mirrors the adoption trends we’ve been seeing. While HuggingFace downloads are obviously very noisy, almost every other adoption metric over time looks strongly correlated with them, especially on U.S. vs. China issues.

As an aside, if this work monitoring the open ecosystem sounds appealing to you, please reach out or leave a comment — I’m thinking about how to scale up our impact in this area!

4. Nations will turn to open models as the only way to get an initial foothold in sovereign AI (and sovereign AI is the real deal)

Sovereign AI has largely been unfolding slowly in the background of frontier AI discussions and the U.S.-China arms race, but it’ll only become more prevalent as AI becomes more deeply embedded in our technological reality. Every wealthy nation will see AI as a direction for influence in addition to a necessity for national security. Open models will likely be the only way to get this off the ground as a real effort, in order to have the local AI community and economy seamlessly integrate with it.

5. Futures where open-source wins the frontier are still possible, but seemingly less likely

The most likely (by far) outcome is for the status quo to continue and for the best open models to lag the best closed models by 6-9months. A large portion of the perpetual catch-up is likely due to the best open model builders constantly distilling their models on the strongest, currently available closed API models, but this direction seems less relevant with the rise of RL. Post-training today is more about the model undergoing experience rather than directly learning from the smartest teacher you can find. The paths to open models winning come through fundamental innovation. This looks like the ability to merge, rotate, and share expert models, a dramatic (100X+) cost reduction in the cost of training, etc. Predicting this before it happens is more of a sci-fi story than a faithful science, as then I’d just go build the damn thing.

6. China’s open model “ecosystem” makes it the most likely place for a discovery around who wins

China has many labs building models on top of their peers’ innovations. This intentional sharing of ideas provides immense benefits relative to Silicon Valley’s quid pro quo where it’s accepted that people go home at the end of their day and chat with some of their friends on the latest technical secrets of their models. The sort of sharing the Chinese companies do, especially considering more of them have closer ties to the nation’s scientific and academic institutions, is the sort of setup that lets new standards converge much faster and breakthroughs be shared. This is another unknown factor, like potential innovation where open models “win,” but it’s important because China has created their own conditions of potential, massive success, and the U.S. has no answer. This divergence in how the ecosystems operate could be nothing in the long-term, but U.S. AI companies cannot do much to compete with it if it takes off.

7. Open models dictate science and diffusion — slower trends than the frontier of AI

The biggest impact in AI in terms of transforming day to day life, and even the world’s power structures, will obviously come from the most powerful and intelligent models. It is fairly obvious then that the open models that end up in closest proximity to this capture the headlines — if an open-weights model does, somehow, happen to claim that title as “the world’s most powerful model,” there will be extreme economic consequences.

In the real world, the one with the highest probability of occurring, open models’ biggest influence will be in two, very slow-moving sectors: 1) fundamental research/innovation and 2) global technological diffusion. I’ve personally realized how much of the excitement I can have for open models is a bit misguided — I’m trying to understand the frontier of AI through the lens of these models, missing the bigger story in how technology slowly reshapes the world’s biggest companies.

Consider when Llama was the open SOTA model, everyone in the U.S. and China did science on Llama, which then impacted subsequent models — even if we didn’t hear directly from Meta on how-so. Now this default is Qwen. Qwen is the anchor of the Chinese ecosystem. Language model research is proceeding extremely fast, which could make the fundamental improvements made in research labs impact the frontier of the technology much faster than usual.

At the same time, the global default for using AI outside of the wealthiest few nations will be to use either free applications like ChatGPT or open weight models. ChatGPT doesn’t fit a lot of business use-cases, so open weight models are a melting pot for innovation that we largely have no visibility into. When we zoom out to a timeline closer to decades, open model’s global adoption seems like a top trend to follow in AI.