The stakeholders start to learn the stakes: predictions for machine learning and automation in 2021

Most of my predictions for automation in 2021 have common people starting to learn how their lives will be impacted, and it’s up to the practitioners to make it fair.

2020 is a year we are all happy to see behind us. The pandemic brought many changes in our lives, but also has changed surprisingly little in how automation impacts our lives. This post details some hypotheses on how I see that changing — as the ice thaws from the pandemic, companies will start to have the flexibility to deploy more autonomous systems. In short, this post has

a longer exploration of the evolving power dynamics around AI,

self driving cars in 2021,

predictions for the next in home robots,

how language processing will play out short-term, and

why reinforcement learning research isn’t really stalling.

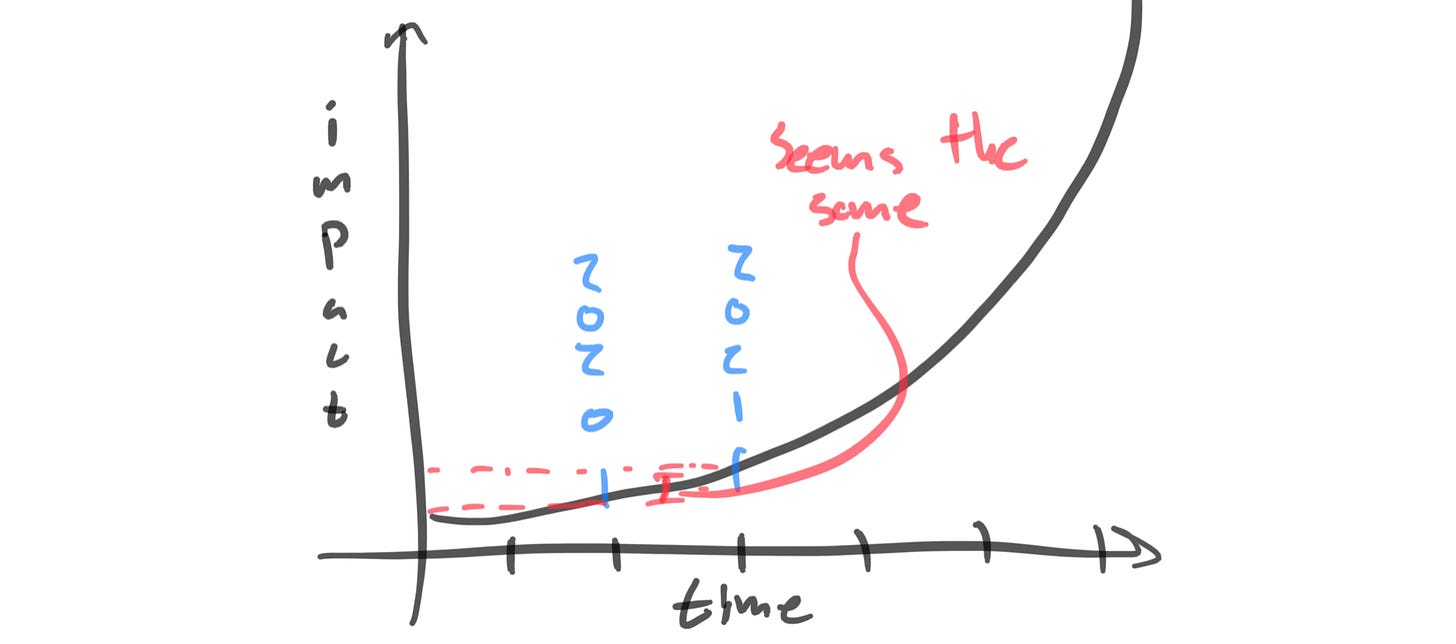

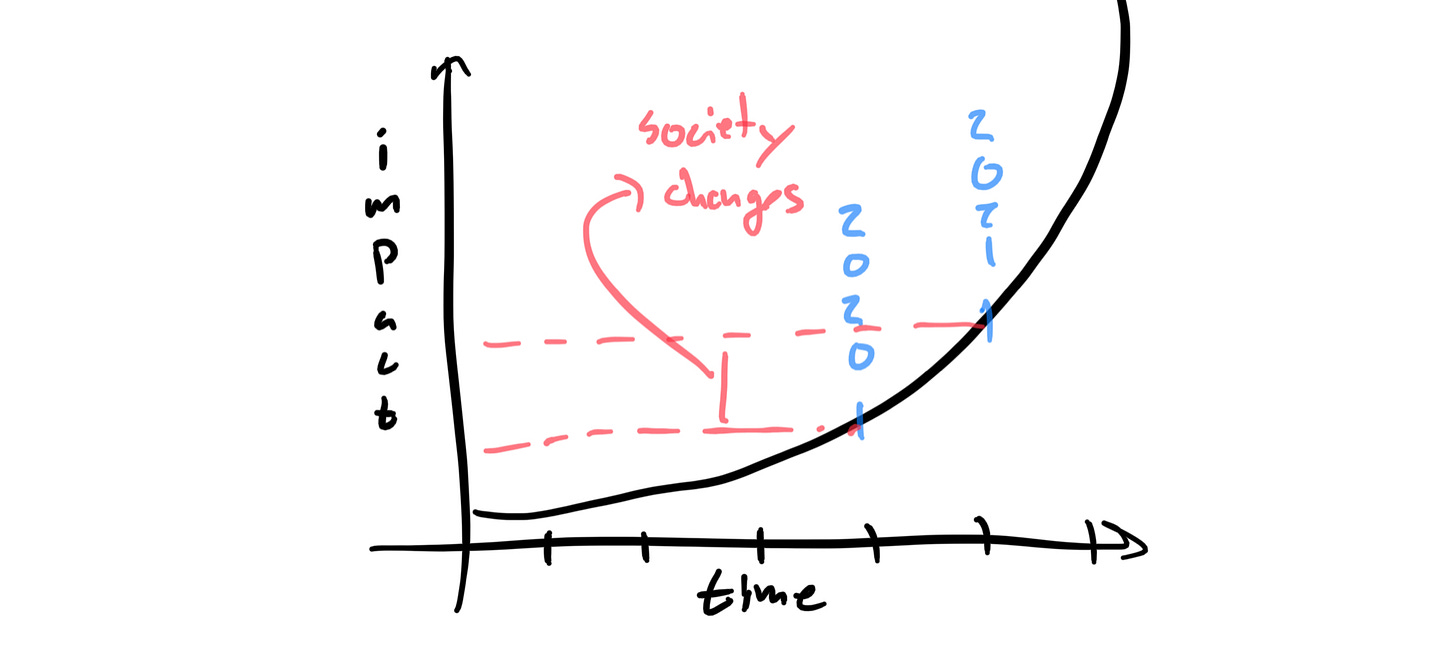

Ultimately, any company that would have benefitted from deploying their systems would have already done so, but we have seen very few new robots in the wild during the pandemic. The impact of these systems depends on where on the s-curve we are — the adoption of artificial intelligence and automation will seem like an exponential for a few years when we are in its prime.

I have visualized the two cases below.

Case 1: coming soon

The automation wave will be cresting in a few years, and we have time to lay the groundwork to steer it. This is if 2021 seems the same as 2020 — so Amazon doesn’t have last-mile drone delivery.

Case 2: happening now

The period of most rapid change is upon us and almost all we can do is watch it unfold (me thinking like this is likely from wrapping up reading Superintelligence, but maybe I should recommend you to watch the newer Superintelligence). In this case, we would see multiple tasks we normally interacted with humans with be replaced by robots by the end of the year.

I am pretty sure we are in case 1, but the fact that is not certain explicates the potential for large scale societal shifts, and relative harm to those who are not in power. It’s really going to be a story of wealth aggregation and long-term health effects, so it won’t be an immediate crisis but one that we are viewing the introduction of.

I don’t think we will see the major uptick of adoption, and this can be seen in the rest of my predictions below. The incremental technological progress does not abdicate the possibility of a major uptick in awareness of the political economy of these forces.

The narratives converge: power, economics, and AI

Political economy: how power dynamics relate with economic practices, law, and society (my working definition, but you can also read Wikipedia’s).

There are currently three major conversations happening within technology and automation.

Anti-trust lawsuits coming from many angles against the biggest companies.

Two-sided regulation discussions (democrats about power and republicans about censorship, broadly).

Political economy of AI ethics.

Without getting into the backstory of each of these, I want to get into how these three separate conversations (with different groups being aware of them) are going to wind up as one central societal conversation about who and what should have power over our digital ecosystems. Really, each one of these conversations is about power on different timescale and from different angles:

Anti-trust: what powers should consumers maintain when operating in a digital world inherently dominated by sets of aggregators?

Regulation: what protections should be set up so individuals and groups (all the way up to nations) are not at risk of technological malpractice?

Ethics: who can say what is right and what is wrong to use with technology?

Underpinning these discussions is the assumption that primarily digital technology can do real harm, and is difficult to track and develop. The latter part makes it substantially easier for established companies to maintain their position.

The ethics discussion over the firing of Timnit Gebru is lingering because of its ties to power (and difficult to discuss because of its linking to discussions of diversity and inclusion). Ultimately, the large technology companies likely do all have a line where they will not allow certain discussions of the implications of their technology to be published internally — this is okay by me, and I think the nation has the resources and wherewithal to develop a separate institution to report on the issues the companies cannot.

The challenging part of this discussion is if the large platforms actively use their reach to manipulate and prevent such autonomous discussions. Major platforms have taken actions towards this (like YouTube banning COVID-19 “misinformation”), and therefore it is hard to know where they will stop. This ties the discussion back to anti-trust and regulation, if the companies determine and control too much of the web traffic than there needs to be new tools to keep them in check (regulation). Bad for consumers in the short term (the basis for anti-trust arguments in the current American law) definitely does not mean that actions of these platforms will be beneficial for society in the long term.

Reaching these do not cross, “go back to go” red-lines of the company executives (too much negative PR to take regarding their new technologies) is where the issues of anti-trust, the need for regulation, and the potential harms of these companies will climax. I feel like we need a new set of metaphors and terminology to discuss this, rather than the three pipelines we have now.

A fourth fold on this story can be the siloization of national internets (different applications and technologies being permitted in geoblocked web-services). 2020 has made it clear that the best of the free internet is behind us, and we have been accelerating towards an impactful year in 2021 in determining the future of our digital lives (the implicit fact is that a new executive branch will accelerate some forces and put others on pause).

The constant coverage of these three stories, and then joining into one will start to teach the public how these risks will affect them. This education of stakeholders is important, but can potentially be tampered with politicians that get to muddy the waters.

Note: here is some recent reading in this space: Google told its researchers to strike a positive tone or The New Laws of Robotics: Defending Human Expertise in the Age of AI (maybe a better title would have been The Political Economy of AI). All three of the themes I have touched on are heavily in discussion by different sets of media, and I am happy to point you to more if you reach out and want to discuss them.

The rest of the predictions

If the pandemic was causing a drastic increase in funding to automation-based companies, why are consumers not seeing the impact? Consider this scenario: if interpersonal contact is so dangerous in a pandemic, why have we not seen more human cashiers and servers this year? My answer is that it is not financially viable for most companies.

Public companies operate on a per-quarter basis where their stock price is heavily influenced by their net profits. Most companies had a reduction in revenue during the pandemic, so any increased costs would take away a relatively larger percentage of profits. Robots cost a lot of capital and would be heavily reflected on an earnings statement if adopted at scale.

It may seem backwards, but as companies rebound they will have more headroom from increased revenues and trimmed staff, so the capital expenditure will be a relatively easier hurdle causing us to see more robots in day to day operations as the economy and public-health sphere improve.

Small self-driving applications

We are going to be able to take self-driving taxi rides on closed circuits.

High-income cities will be the initial places for these applications (and maybe we will see the insanely subsidized prices like the early Uber-Lyft wars). For example, the CEO of Waymo openly talked about their plans to roll-out more taxi services in the next couple of years. This is possible because on closed circuits (think environments where the companies have explicit maps drawn of 100% of the roadways before enabling autonomous cars) cars easily gain multiple 9s of reliability. I mean, with Amazon in the game everything is bound to get accelerated. Sorry Tesla, you are not winning this game in terms of being first-to-market, but I still think you are winning in the marketing point of view.

Home assistants that move

Things like the Amazon Echo and Google Home will start to act in the physical world.

I have long been thinking about what will be the next robot in the home (still waiting for the successor to the Roomba), and I repeatedly think the smart speakers are closest to doing so. Combining these home-internet touchpoint with robots like video call assistants, and it is the link merging a partially digital world with a reemerging in-person workplace. Interfaces between fully remote operation (in the workplace and in personal lives) will experience the Zoom-explosion that happened in 2020. The hardest part is bridging the gap from the floor to the human point of view — I don’t think many people want to talk to their smart speaker like a dog, and an in-home flying robot is nowhere near practical nor wanted yet.

NLP train continues

Language processing will continue its growth in usefulness, parameter count, sketchiness, and all.

Language processing seems to be in its heyday. This conversation will continue to grow into 2021. The easy trend to notice is that we will hit a 1 trillion parameter language model (less than an order of magnitude growth from 2019, where the success of the models was lucrative enough for Google to use them in every search query). The harder trend to tease at is what this will affect — big companies will use them, but smaller agents will likely make harder to track blunders.

NLP seems to be the nearest touchpoint for interactions with machine learning (many technologies deploy computer vision, but users don’t really interact with it in a feedback loop). Things like automated writing will start to go onto the marketplace (and money will be made with them), forms of this technology will be used for deepfakes, and more. Language processing also will drift down into things like chatbots for customer service (Facebook acquired a related company for $1 billion) and even mental health tools (scary). The feedback effect of how using these affects humans is more likely to change peoples lives than some other one-off technology because it will slowly redefine human relationships as well.

Broadening of the scope of RL

Reinforcement learning isn’t going to be making breakthroughs “at the pointy end” (theory/continuous control), but rather in applications.

The sense from in the Deep RL community is that progress is slowing down a bit on a couple of canonical problems (which is measured on peak-performance on a series of walled off Mujoco baselines not increasing much). I don’t really view this as a long-term risk for the field in terms of impact and investment, but maybe some of the people who are metric-obsessed will leave and that would be a long-term win. The two things that will happen are more focus on useful applications and consolidation of research evaluation.

RL is useful in a few real world tasks to date where the problem specification is way too hard to solve by optimal methods and the dynamics are well-defined (e.g. power grids) and there are bound to be more cases where this is true. We will see a couple more DeepMind-like uses of RL (no I don’t count the Loom balloon control on this list) where an engineering team applies the useful side of RL to solve problems. I would expect them to be in biology/healthcare space, especially in problems that can explored digitally.

The less important second outcome for RL in 2021 will be a bit of consolidation of research — this means the community will emerge with a better common set of problems to work on for years in the future. What is needed is a problem that is accessible to the public (don’t need to pay for a simulator) and has a large learning curve with multiple levels of accomplishment for agents. This means that people working in the field can work on the same problem for multiple years and keep getting better — there will not be a simple yes or no metric for when it is solved.

What did I miss?

More from the author

Some more things I published:

Some reflections on being a PhD student — I am trying to get to the bottom of why we all feel like we have a million things going on at once and not quite the right tools to extinguish them.

My notes from the biggest machine learning conference of the year, NuerIPs — a deep dive on recent advances in robot learning and deep reinforcement learning.

Hopefully, you find some of this interesting and fun. You can find more about the author here. Tweet at me @natolambert or follow the blog @demrobots, reply here. I write to learn and converse. Forwarded this? Subscribe below.