On China's open source AI trajectory

Notes and predictions for the next phase of Chinese (open) AI models.

Hello everyone! I’m coming back online after two weeks of vacation. Thankfully it coincided with some of the slowest weeks of the year in the AI space. I’m excited to get back to writing and (soon) share projects that’ll wrap up in the last months of the year.

It seemed like a good time to remind people of the full set of housekeeping for Interconnects.

Many people love the audio version of the essays (read by me, not AI). You can get them in your podcast player here. Paid subscribers can add private podcast feeds under “manage your subscription” where voiceover is available for paywalled posts.

The Interconnects Discord for paid subscribers continues to get better, and is potentially the leading paid perk amid the fragmentation of Twitter etc.

We’re going to be rolling out more perks for group subscriptions and experimental products this fall. Stay tuned, or get in touch if group discounts are super exciting for your company.

For the time being, I’m planning trips and meetups across a few conferences in October. I’ll be speaking at The Curve (Oct. 3-5, Berkeley), COLM (Oct. 7-10, Montreal, interest form), and the PyTorch Conference (Oct. 21-24, SF) on open models, Olmo, and the ATOM Project, so stay tuned for meetups and community opportunities. On to the post!

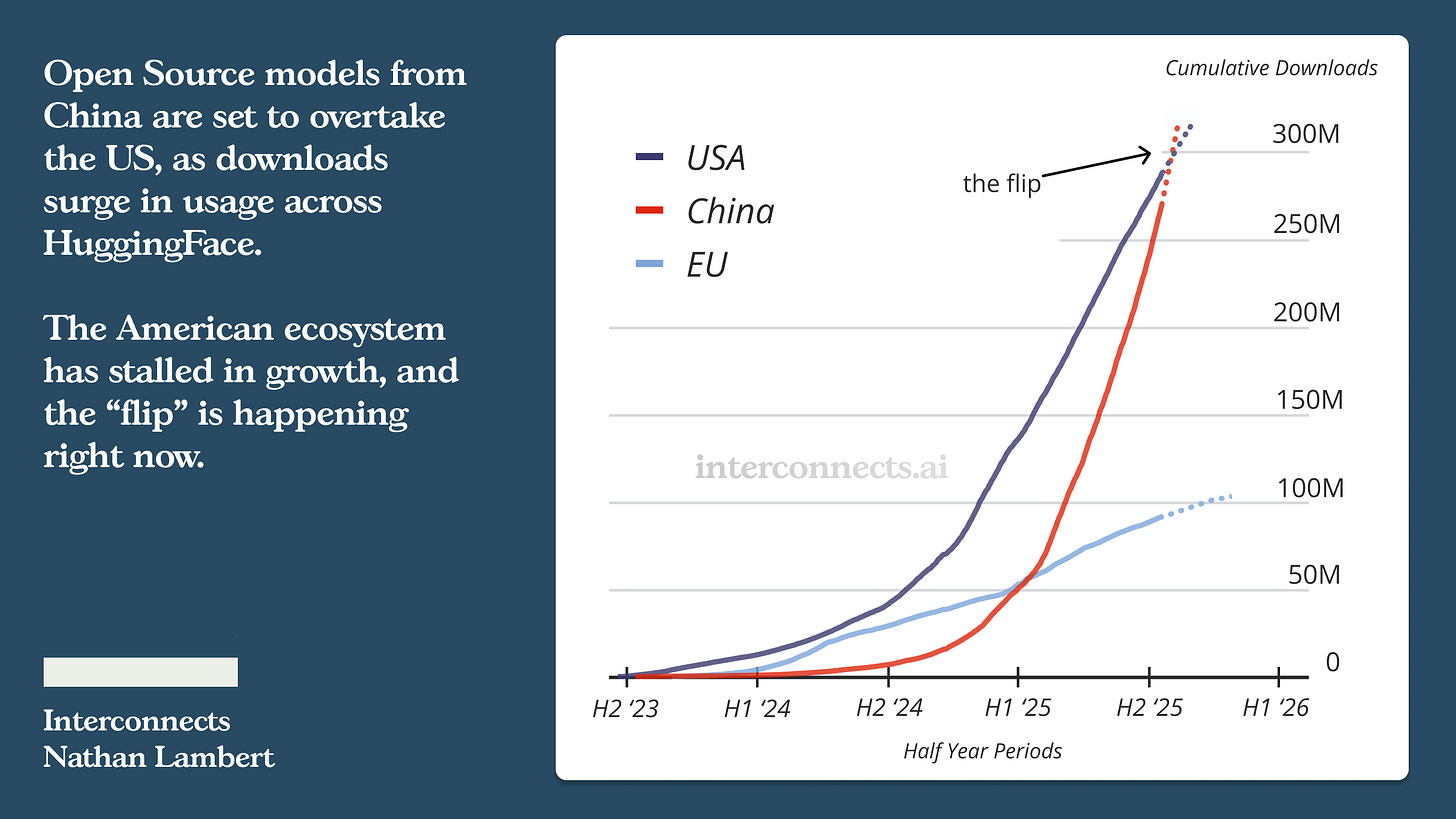

China is maneuvering to double down on its open AI ecosystem. Depending on how the U.S. and its allies change culture and mobilize investment, this could make the dominance of Chinese AI models this summer, from Qwen, Kimi, Z.ai, and DeepSeek, looks like foreshadowing rather than the maximum gap in open models between the U.S. and China.

Until the DeepSeek moment, AI was likely a fringe issue to the PRC Government. The central government will set guidelines, rules, budgets, and focus areas that will be distributed and enforced across the decentralized government power structures. AI wasn’t a political focus and the strategy of open-source was likely set by companies looking to close the gap with leading American competitors and achieve maximum market share in the minimum time. I hear all the time that most companies in the U.S. want to start with open models for IT and philosophical reasons, even when spinning up access to a new API model is almost effortless, and it’s likely this bias could be even higher internationally where spending on technology services is historically lower.

Most American startups are starting with Chinese models. I’ve been saying this for a while, but a more official reference for this comes from a recent quote from an a16z partner, Martin Casado, another vocal advocate of investment in open models in America. He was quoted in The Economist with regards to his venture portfolio companies:

“I’d say 80% chance [they are] using a Chinese open-source model.”

The crucial question for the next few years in the geopolitical evolution of AI is whether China will double down on this open-source strategy or change course. The difficulty with monitoring this position is that it could look like nothing is happening and China maintains its outputs, even when the processes for creating them are far different. Holding a position is still a decision.

It’s feasible in the next decade that AI applications and open models are approached with the same vigor that China built public infrastructure over the last few decades (Yes, I’m reading Dan Wang’s new book Breakneck). It could become a new area that local officials compete in to prove their worth to the nation — I’m not sure even true China experts could make confident predictions here. A large source of uncertainty is whether the sort of top-down, PRC edicts can result in effective AI models and digital systems, where government officials succeeded in the past with physical infrastructure.

At the same time as obvious pro-AI messaging, Chinese officials have warned of “disorderly competition” in the AI space, which is an indirect signal that could keep model providers releasing their models openly. Open models reduce duplicative costs of training, help the entire ecosystem monitor best practices, and force business models that aren’t reliant on simple race-to-the-bottom inference markets. Open model submarkets are emerging for every corner of the AI ecosystem, such as video generation or robotic action models, (see our coverage of open models, Artifacts Logs) with a dramatic evolution from research ideas to mature, stable models in the last 12-18 months.

China improving the open model ecosystem looks like the forced adoption of Chinese AI chips, further specialization of companies’ open models to evolving niches, and expanded influence on fundamental AI research shared internationally. All of these directions have early signs of occurring.

If the PRC Government wanted to exert certain types of control on the AI ecosystem — they could. This Doug Guthrie excerpt from Apple in China tells the story from the perspective of international companies. Guthrie was a major player in advising on culture changes in Cupertino to better adapt Apple’s strategy to the Chinese market.

“When you stake your life, your identity, on and around certain ideas, you sort of fight for them,” Guthrie says. “Xi Jinping kind of broke my heart… I was sitting there, in China, in my dream job, and I’m watching Xinjiang’s internment camps. I’m watching China tearing up a fifty-year agreement over Hong Kong.”

Apple, meanwhile, had become too intertwined with China. Guthrie had been hired to help understand the country and to navigate it. And Apple had followed through—very successfully. But it had burned so many boats, as the saying goes, that Guthrie felt its fate was married to China’s and there was no way out. “The cost of doing business in China today is a high one, and it is paid by any and every company that comes looking to tap into its markets or leverage its workforce,” he later wrote in a blog. “Quite simply, you don’t get to do business in China today without doing exactly what the Chinese government wants you to do. Period. No one is immune. No one.”

China famously cracked down on its largest technology companies in late 2020, stripping key figures of power and dramatic amounts of market value off the books. AI is not immune to this.

The primary read here is that the PRC leadership will decide on the role they want to have in the open-source AI ecosystem. The safe assumption has been that it would continue because the government picked up a high-impact national strategy when it first started focusing on the issue, already seeded with international influence.

To formalize these intentions, the Chinese government has recently enacted an “AI+” plan that reads very similarly to the recent White House AI Action Plan when it comes to open models. The AI+ plan idea was first proposed in March 2024 and was just approved in its full text on July 31, 2025. The AI+ plan, when enacted by local officials, lays out goals for the AI industry in how many open models to have at different tiers of performance and some funding mechanisms for nurturing them.

This is right in line with other comments from party officials. Chinese Premier Li Qiang, second-ranking member of the Politburo Standing Committee, made comments in March directly supporting open-source models. From the Wall Street Journal:

Li pledged that China would boost support for applications of large-scale AI models and AI hardware, such as smartphones, robots, and smart cars.

China’s top economic planning body also said Wednesday that the country aimed to develop a system of open-source models while continuing to invest in computing power and data for AI.

An excerpt from Beijing’s city plan as part of the overall AI+ initiative, translated by GPT-5 Pro, has interesting, specific goals:

By end-2025: implement 5 benchmark application projects at a world-leading level; organize 10 demonstration application projects that lead the nation; and promote a batch of commercializable results. Strive to form 3–5 advanced, usable, and self-controllable base large-model products, 100 excellent industry large-model products, and 1,000 industry success cases. Take the lead in building an AI-native city, making Beijing a globally influential AI innovation source and application high ground.

The goal of this is to:

Encourage open-source, high-parameter, ‘autonomous and controllable’ base foundation models, and support building cloud hosting platforms for models and datasets to facilitate developer sharing and collaboration.

Beyond the minor translation bumpiness, the intentions are clear. The goal of the A+ plan is clear with multiple mentions of both open-source models and an open ecosystem with them where the models can be adopted widely. The ecosystem of models can make the impact of any one individual model greater than it would be alone.

The Chinese government having centralized power has more direct levers to enact change than the White House, but this comes with the same trade-offs as all initiatives face when comparing the U.S. vs. China’s potential. I won’t review all of the differences in the approaches here.

Where the Chinese Government enacts top level edicts that’ll be harder to follow from the West, there are numerous anecdotes and interactions that highlight in plain terms the mood of the AI ecosystem in China. I’ve routinely been impressed by the level of direct engagement I have received from leading Chinese AI companies and news outlets. Interconnects’ readership has grown substantially in China.

Chinese companies are very sensitive to how their open contributions are viewed — highlighting great pride in both their work and approach. The latest case was via our China open model rankings that got direct engagement from multiple Chinese AI labs and was highlighted by a prominent AI news outlet in China — 机器之心/Synced. They described Interconnects as a “high-quality content platform deeply focused on frontier AI research.” (This Synced post was translated and discussed in the latest ChinaAI Newsletter)

When intellectuals, influencers, and analysts I follow talk directly to technical members of the AI workforce in China, they sound like what we would expect — people who want to build a great technology. Jasmine Sun had a great writeup on her trip that had some anecdotes on AI in China. She asked “Do you guys worry about AI safety?”

“We don’t think about risks at all.” …

Continuing from Jasmine:

This was the first of several conversations that gave us a distinct impression of the Chinese tech community. Spirits are high, and decoupling policies like export controls only fuel their patriotic drive.

At the same time, America still represents a covetable life, despite the current political tumult:

To be clear, our researcher friend made clear that working at a top US AI lab was still the most desirable option.

In so many ways, trying to precisely map China’s next steps in AI is extremely challenging. Can they convert their lead in energy infrastructure to more total AI compute? Can they build their own AI chips? Will they take the frontier of performance with their talented population and a different approach? All of this is up for debate.

The intrigue here is exemplified by the abundant interest in sparse news stories on how DeepSeek is training some AI model with Huawei chips. In many ways, these new chips working would be a bigger story than the original DeepSeek model, but all signs point to expected experiments with domestic chips, where China’s leading AI models are likely to be trained on Nvidia and other Western chips for the foreseeable future. I do not expect DeepSeek R2 to be trained on Huawei’s hardware.

China’s hardware investment will take a lot longer to play out than open model strategies, but if China pulls it off — along with its other investments, such as self-driving cars and robots — their practical lead in AI could come for more areas. Open models could be China’s beachhead in a bigger technological resurgence with AI.

Without major changes to Western investment in open models, we’re approaching a status quo in 2026 and beyond where:

Chinese open models would continue to increase their lead in performance (and adoption) over American counterparts. This will manifest in many ways. One example is how startups in Silicon Valley built on stronger Chinese models will be offering services that compete with entrenched, handicapped Fortune 500 companies wary of adopting these models in their services. This could make some subareas of AI disruption feel particularly intense.

The Chinese open ecosystem’s density of knowledge and sharing would translate into increased scientific and academic impact. China’s share of conference papers at leading AI conferences is already rapidly on the rise, and having an ecosystem built around substantially better models than their Western counterparts could lead this numerous research growing also to be impactful. Better base models allow more interesting RL and agentic research today, and the list of areas reliant on high-performance models is likely to only grow longer with time.

A proliferation of strong open models would make it difficult to restrict the presence or availability of many forms of AI. We do not have the government tools, incentives, nor culture to successfully prevent digital goods from China (or elsewhere) entering the U.S. economy. Many forms of AI governance and regulation in the United States and the rest of the world may need to be reconsidered, where many jurisdictions have looked to control and understand the development of “frontier AI.” Regulation needs to be approached for a world enmeshed in powerful AI models, rather than trying to control access or the releases of a few.

These realities all paint a clear picture that bends the association of open models from “soft power” to just “power.” Continuously releasing strong open AI models could allow Chinese companies to shape the technology interfaces, services and reality around the world. Where 2024 was about research on open models, and 2025 the professionalization of them, 2026 could be where we begin to see clear impacts of their power through endless distribution.